MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

Do you know any people with myasthenia gravis? Do you know what myasthenia gravis is? Did you know it has a very well-defined cause that was discovered many decades ago, and that treatments available are very effective?

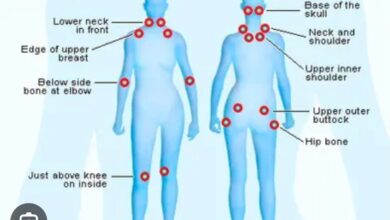

Myasthenia gravis is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by muscle weakness that occurs in the eyelids, neck, throat, arms, and lower extremities. This weakness comes on gradually as the day progresses finally resulting in drooping eyelids, difficulty speaking and swallowing, trouble breathing, and the inability to hold your head up, use your arms, or walk. It is seen most often in women under 40 and men over 60. These symptoms all occur because of a problem at the junction of the nerves and muscles.

A nerve-muscle junction is called a synapse. Nerves are made up of bundles of fibers that form axons. At the end of an axon, nerve fibers separate into finger-like fibers called dendrites. Dendrites are located next to the other half of the neuromuscular junction, the surface of the muscle fibers. On the surface of the muscle fibers are receptors, specialized cells that receive a signal from the nerve endings. The signals coming from the nerves come in the form of a chemical, acetylcholine (ACH), a neurotransmitter. The brain sends a signal to the nerves and ACH is released from the dendrites. ACH attaches to the muscle fiber receptors, and causes the muscles to move and function as they are supposed to. A schematic example of a normal nerve-muscle junction: Nerve—ACH—Muscle movement.

In MG, the nerve-muscle junction does not function correctly. MG is an autoimmune disease, that means the immune system produces antibodies (acetylcholinesterase) that attach to the muscle receptors. The muscle receptors are blocked so the ACH produced by the nerves is prevented from stimulating the receptors, and the muscles become weak or can’t function properly. Thus, we have this schematic example in myasthenia gravis:

Nerve—Acetylcholinesterase blocks ACH receptors—Weakness or no muscle movement

Where do these antibodies originate? The Thymus gland. Have you ever heard of the thymus? Well, it’s a part of the immune system located in the upper chest, just below the thyroid gland. It produces T-cells. By puberty most Thymus glands have stopped functioning and shrunk in size so MG doesn’t occur. Some however, do not. They function on their own to produce antibodies that block nerve-muscle junctions, causing the symptoms of MG to appear.

Drooping eyelids (ptosis), inability to talk normally, or swallow, difficulty holding your head up (it will fall forward or to the side), or weakness of the extremities. Not everybody has total body weakness. But eventually the disease progresses and uninvolved muscles become involved.

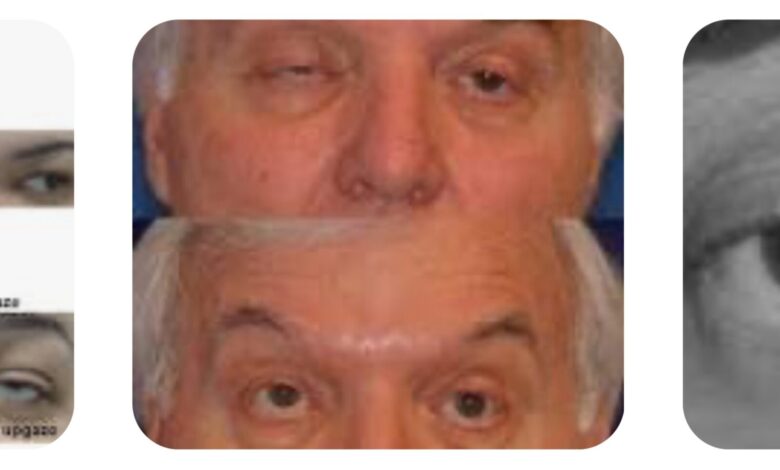

I recall in my first year of med school (1965-‘66), during a physiology lecture, a visiting speaker, who was a specialist in MG, brought a gentleman to the lecture to display his symptoms and see how quickly a drug he gave him worked. The speaker was Dr. Edward Tether who, in Indianapolis, had developed quite a busy practice of mostly MG patients. He participated in many clinical drug trials so he knew about, and had access to, the latest and greatest treatments. I recall his patient was a stocky man wearing a white shirt and dark pants whose eyelids were drooping so badly he had to be led onto the lecture platform. Dr. Tether asked him to open his eyes. He could not. He asked him to hold his arms straight out in front of him. He could hold them for a few seconds, but as he held them out in front, they gradually drifted downward until they were at his side.

Dr. Tether then gave him a shot of Tensilon (edrophonium), a drug that inhibited the action of the acetylcholinesterase antibodies. Within seconds the man could open his eyes normally and hold his arms up for a reasonably long time. ie. All his MG symptoms disappeared. This 22 yo freshman med student was impressed. The Tensilon Test was the diagnostic test of choice for decades, but is not used now because many patients had significant reactions to Tensilon. MG is now diagnosed through blood tests and electromyogram (EMG) studies.

Treatment of MG has two goals: 1. To reverse symptoms. 2. Bring about remission. Reversing symptoms is the more frequent route, because not every patient goes into remission.

Drugs that block ACH antibodies are the agents that reverse symptoms. Mestinon is the drug of choice (pyridostigmine), physostigmine, neostigmine, edrophonium—these drugs reverse weakness and restore normal muscle function. They are taken daily to control symptoms.

Immune system suppressants that prevent antibody production. Corticosteroids (prednisone), Imuran, cyclosporine, mycophenulate (new to me). These drugs are taken long term to suppress antibody production.

Drugs targeted specifically for MG. Soliris, Zilbrysq, Vyvgart, Rystiggo (never heard of these and have no knowledge of their use).

Other treatments for remission. Removal of the Thymus gland, plasmapheresis (cleansing of antibodies from the plasma-liquid part of blood), IVIG—infusion of high doses of gamma globulin).

Myasthenia gravis, a chronic autoimmune, neuromuscular disease, characterized by weakness of affected muscles. MG has the potential to go into remission, and is normally not fatal. If treated early, remission is more likely. Multiple highly effective treatments are available.

References: Linton DM, Philcox D. Myasthenia Gravis Dis Mon 1990 Nov;36(11):593-637.

Estevez DAG, Fernandez JP. Myasthenia gravis. Update on diagnosis and therapy. Med Clin (Barc) 2023 Aug 11;161(3):119-127.

Torre SM, Molinero IG, Giron RM An update on myasthenia gravis. Semergen 2018 July-Aug;44(5):351-354.

Www. google.com drugs for myasthenia, IVIG, Myasthenia gravis demographics, axon, dendrite, thymus gland, thymus and myasthenia gravis, Tensilon, Tensilon drug test.