Alzheimer’s Disease is the diagnosis often given to patients who exhibit loss of memory, personality and behavior changes, confusion, and difficulty making decisions. However, that designation would be incorrect in a large percentage of patients. Instead, they should actually be classed as having a Dementia, of which Alzheimer’s is just one type.

Dementia is a “universal” term that implies the patient has a “cognitive impairment.” Cognition is the process of using the brain for intellectual functioning—thinking, reasoning, concluding, and remembering. In laymen’s terms, “cognitive impairment” means the patient is showing symptoms of memory loss, poor judgement, communication difficulties, and personality changes. They have trouble handling complex tasks, planning and organizing, and solving problems. Early in the course of dementia, the symptoms are very subtle and are sometimes dismissed as being due to old age. But as time passes, the symptoms worsen until the problem cannot be denied.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is just one of the many types of dementia. Between 50 and 75% of dementia patients have Alzheimer’s. It is a “diagnosis of exclusion.” That means when every other possible cause of dementia has been ruled out (excluded), the doctor is left to conclude the patient has Alzheimer’s. To determine AD with certainty, a sampling (biopsy) of brain tissue is required. AD shows characteristic changes in brain cells that are detectable only under microscopic examination. However, that procedure is usually not done on live patients and is reserved for an autopsy after death. So in a living person, AD is diagnosed by eliminating all other detectable causes. Thus you could rightly conclude that some demented patients are just given this “wastebasket diagnosis” without any attempt to determine a more specific cause.

I have identified at least thirteen causes of dementia. Some of them are quite rare, but are mentioned for the sake of completeness. I will list each and give a brief description thereof. One thing each has in common, of course, is the complex of symptoms present in dementias-memory loss, poor judgement, communication difficulties, and personality changes.

The disorders in which dementia is a significant component are as follows:

Alzheimer’s Disease (50-75%)—a diagnosis made by excluding other causes. Depression is a big accompaniment, and early on, AD patients may be mistakenly thought to be depressed. As AD worsens, memory, judgement, and communication decline, and patients require total help with daily living. AD patients hide their symptoms well by deflecting questions and answering questions with a question. I had a patient in his mid-60’s who never gave a straight answer to a direct question. One day when he redressed after his physical, he put his shirt and pants on backwards and was completely unaware he had done so. He was admitted to a nursing home 3 months later and died after being there for two years. 50-75% of Dementias are Alzheimer’s.

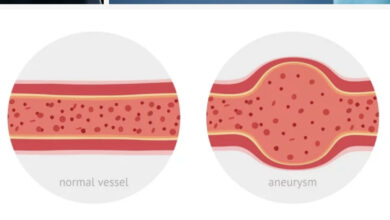

Vascular Dementia (20%)—arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) of the blood vessels reduces blood flow to the brain. Vascular disease causes TIA, stroke, confusion, disorientation, trouble completing tasks and poor concentration accompanied by dementia. Vision problems and hallucinations are common. Diagnosis is confirmed by changes in the brain seen on MRI studies.

Lewy Body Dementia (5%)—is caused by protein deposits in nerve cells. Memory loss, motor and muscle weakness, decision-making problems, difficulty concentrating, hand tremor, trouble walking, visual hallucinations, and trouble falling asleep are symptoms. Special imaging studies (PET, SPECT scans) can assist in making the diagnosis.

Parkinson’s Disease Dementia—is similar to Lewy Body Disease with motor and cognitive problems. Slow movements (bradykinesias), weakness, tremor (pill rolling), shuffling gait, blank-face stare, reduced voice volume, and rigidity of extremities usually precede dementia by many years. Dementia appears as a late symptom in Parkinson’s.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (Mad Cow Disease)—a rare cause of dementia. Depression, withdrawal, and mood changes occur early. As the disease progresses, confusion, memory loss, agitation, physical disabilities, hallucinations, and finally psychosis develop. CJD is diagnosed using EEG, MRI, and spinal fluid analysis combined with the symptoms and physical findings. The true diagnosis can only be determined by brain biopsy at time of autopsy.

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome—is a brain disorder caused by a lack of Vitamin B-1. It’s most common cause is alcoholism, but malnutrition and chronic infections can also cause it. It is “technically not a form of dementia,” but patients have trouble processing information and learning new skills, and memory loss, all symptoms of dementia. The diagnosis is based on a history of nutritional deficiency or alcoholism.

Frontotemporal Dementia (Pick’s Disease) (5%)—affects younger people. The front and side parts of the brain that control language and behavior are affected. These areas shrink as noted by MRI studies. Memory loss, communication, and physical ability decline as the disease progresses. I have a golfing acquaintance who had this disorder. On a golf trip he was short-tempered, abrupt in speech, and said mean things about others, behavior he had not previously shown. Six months later, he was diagnosed with Frontotemporal Atrophy with dementia.

Huntington’s Disease—a genetic disorder that causes dementia. Also seen are difficulty walking, balancing, jerky movements (chorea), and impaired movement. It occurs in adolescents and people in their 30’s and 40’s. Diagnosis is made by family history and typical physical findings.

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus—an excessive build up of spinal fluid in the cavities (ventricles) of the brain. It occurs as a result of over-production of spinal fluid or a blockage at the point where spinal fluid exits the brain. As more and more fluid is produced, the brain cells become compressed by the increasing pressure, and neurologic symptoms and dementia ensue. It is diagnosed by CT or MRI studies and if detected early, can be treated successfully by surgery.

Mixed Dementia—a common situation where more than one cause exists and symptoms typical of different dementias are present. Most patients have difficulty speaking and walking, but some also have memory loss and disorientation while others have behavior and mood changes. Experts say as high as 45% of dementia patients have mixed type.

Multiple Sclerosis HIV Mild Cognitive Impairment—MS, HIV, and MCI are listed as “other causes of dementia,” but are either chronic diseases in which dementia and delirium can occur or are an early harbinger of things to come later when full-blown Alzheimer’s Disease develops.

Of course this list is not comprehensive, but it covers the majority of the causes of dementia. Ten percent of diabetic patients develop dementia. Chronic exposure to metals and CTE, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, are other causes.

But the physician must be wary of any new, unusual neurologic symptom or finding the patient develops, and not dismiss it as an aging change. I had a 79-year-old retired attorney patient who came in the office confused, forgetful, and disoriented. He could walk, but not well. His son, who accompanied him to my office, was very concerned about him. These symptoms had developed suddenly and were gradually worsening. On questioning, he was disoriented, couldn’t subtract numbers, couldn’t remember three objects or the U.S. Presidents. His balance was unsteady, and with his eyes closed, he nearly fell when standing with his feet together. He obviously had something serious wrong so I sent him to the hospital for a stat CT of the head. This showed large blood clots (subdural hematomas) on both sides of his brain. He was immediately taken to the operating room where a neurosurgeon drained both blood clots.

After surgery, his symptoms gradually eased and dementia symptoms resolved. I later learned that two weeks before, while on Spring break in Hawaii, his grandkids had talked him into going down a water slide. On the way down, he bumped both sides of his head on the side wall of the slide. This seemingly minor trauma caused bilateral subdural hematomas, or blood clots between the skull and the surface of the brain. After surgery his acute symptoms resolved, but he was never as mentally sharp or quick as he had been previously.

It is conceivable that his symptoms could have been passed off as “getting old,” but any competent physician would react otherwise. He was demented, yes, but the onset was sudden, the symptoms severe, and he was rapidly worsening. It was obvious he had something wrong. It just wasn’t obvious what until the CT was done.

More typically, dementia is gradual in onset with symptoms taking months or years to develop. And it is usually a caregiver, spouse, or other family member who notices the problem. Whenever a patient himself/herself came to the office alone thinking they had Alzheimer’s, they almost never did. AD patients are normally unaware of the problems others easily recognize, and they vehemently deny there’s anything wrong. “Senior moments” do occur to people all the time. You enter a room and forget why you walked in, or you forget why you said a certain thing, or you misplace your car keys, but you’re fully aware of your mistake. That is not dementia. Alzheimer’s patients remember who was their best childhood friend, but can’t remember something their spouse told them minutes before.

Multiple “mental status” tests have been devised to detect and confirm dementia. I think whichever test works well for you is the one to use consistently. A popular and reliable test is the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) in which patients draw the face of a clock, subtract 7 from 100 and proceed downward, name and recall three objects, and interpret sayings, among other items. These questions test memory, reasoning, organization, and spatial relationships. Diagnosing dementias is fairly straightforward, but the big problem comes when treatment begins.

None of the causes of dementia can be cured. Each involves a significant degenerative change in the brain cells, and once it has taken hold is not reversible. These are all bad diseases that progress over time. Patients become less and less able to move around, get weaker, have trouble breathing and eating, and can’t swallow. They develop urinary tract infections, pneumonia, bed sores, become septic (bloodstream infection), and die. It’s a downhill spiral that can go on for years.

However, there is some encouraging news. There is a “positive association between participating in cognitively stimulating leisure activities and a decrease in the incidence of dementia and improved cognition test performance.” This means the more you use you intellectual abilities and exercise your brain, the less likely you are to develop dementia. That’s a nice consolation, but you still hear of numerous cases of highly intellectual people becoming demented. So there is concern about the validity of that theory. But I’m trying hard to see if it’s true. I hope it is; otherwise I’m wasting brain energy. Time will tell.

References: Cunningham EL, McGuinness B, Herron B, Passmore AP, Dementia Ulster Med J 2015;84(2):79-87.

Higgs P, Gilleard C, Ageing, dementia and the social mind:past, present, and future perspectives. Social Health Illn 2017 Feb;39(2):175-181.

Farfel JM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease frequency peaks in the tenth decade and lower afterwards. Acts Neuropathol Commun 2019 Jul 3;7(1):104.

https://www.alzwisc.org/types/dementia

https://www.healthline.com/health/types-dementia

https://www.verywellhealth.com/types-of-dementia

Matyas N, et al. BMJ Open 2019 Jul 2:9(7)

Ryu JC, Zimmer ER Neurotherapeutics 2019 Jul 3.