HYDROCEPHALUS—“Water on the Brain”

Recently, I’ve had occasion to know two people who were diagnosed with Hydrocephalus. Today, this is still a serious, relatively uncommon problem, but as the population of elderly folks increases, the frequency of this disorder stands to increase. Hydrocephalus is the abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid, CSF, in the cavities and spaces of the brain and spinal cord. “Hydro” is the derivative for water while “cephal” is the root designate for brain or head. Thus, Hydrocephalus literally means “water on the brain.” CSF is the “water” that surrounds, bathes, and cushions the brain and spinal cord.

Hydrocephalus can occur at any age. Pediatric hydrocephalus occurs in less than 1% of live births, and is the infant born with a large head or one that is increasing in circumference faster than normal. These infants have all sorts of problems neurologically and developmentally and require immediate surgery to correct the problems hydrocephalus causes. Fifty-seven years ago, as a senior medical student on my pediatric rotation, we were required take a field trip to the Muscatatuck State Hospital, in Muscatatuck, Indiana, where dozens of children were hospitalized chronically for advanced hydrocephalus or for failed, unsuccessful treatment. It was very sad and sobering to see dozens of children, from infants to teen agers lying in beds or cribs, with heads so large they could not raise them off the bed. Some were conscious, some were comatose, but all had serious neurologic disabilities.

Adult/geriatric hydrocephalus is a different condition. There is still water on the brain, but unlike the soft, flexible, expandable skull of an infant or child, the adult skull is fixed in size and shape and can expand very little or not at all. Instead of the skull enlarging, as CSF increases in volume and has nowhere to escape, in adults the brain tissue becomes compressed more and more. As compression increases so do symptoms. Headaches, balance and coordination problems, vision disturbances, cognitive difficulties, incontinence, nausea and vomiting, sleepiness and mental and physical sluggishness are some of the many symptoms related to hydrocephalus. Some people simply become forgetful, irritable, and slow mentally, but over time these symptoms progress.

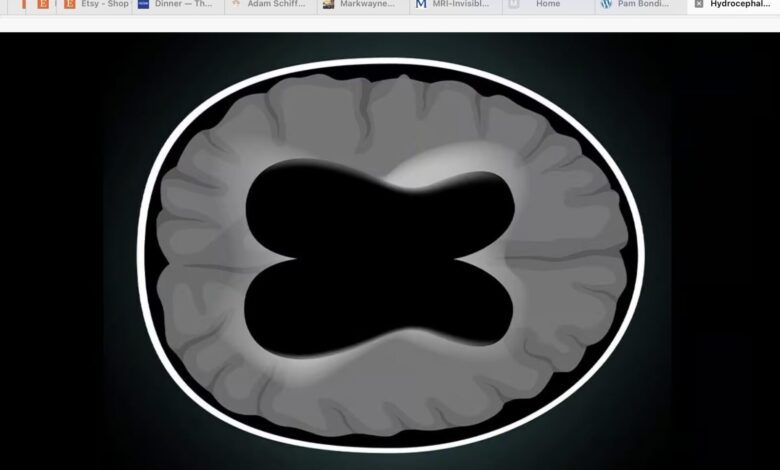

Hydrocephalus starts in the fluid-filled cavities of the brain called “ventricles.” Large lateral ventricles lie deep within the cerebral hemispheres and connect to a 3rd ventricle which lies within the brainstem and to a lower 4th ventricle The ventricles are lined by special cells called the choroid plexus which produce and release cerebrospinal fluid, CSF, into the ventricles. CSF flows freely in the ventricles and is released onto the outer surface of the brain and spinal cord to bathe and cushion these structures. Spinal fluid is clear and colorless resembling water.

If CSF is over-produced, or if it cannot be reabsorbed completely, it has nowhere to go and remains in the ventricles. As it accumulates, CSF begins to compress the brain tissue. When compression gets bad enough, neurological symptoms develop. This pressure must be reduced so permanent brain damage (i.e. irreversible neurologic symptoms) does not occur.

Hydrocephalus is diagnosed by either a CT or an MRI of the brain. It is easily diagnosed through these studies, but the cause is often not determined. In fact, there are many causes, but the cause does not usually influence therapy. Adult hydrocephalus can be acquired such as after head trauma causing blood clots or bleeding, or as the consequence of an illness such as a brain tumor, meningitis, or stroke. Imaging studies will usually identify the cause in such instances. Other cases will not identify a cause, but it is noted that hydrocephalus is present. These folks present with symptoms resembling Alzheimer’s Disease or Parkinson’s Disease and have Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (iNPH). These patients have “a complicated triad of cognitive, gait, and urinary abnormalities” which contribute to difficulty in diagnosing the condition. The doctor has to suspect it to be able to diagnose it.

Hydrocephalus is further designated primary or secondary. Primary hydrocephalus is that found in infants and children and is congenital/genetic in origin. Secondary hydrocephalus is that acquired as a result of head trauma, infection, or brain hemorrhage. In almost all cases, treatment is the same.

The goal of treatment is to re-establish the egress (passage out) of CSF trapped within the brain ventricles so as to prevent further compression of the brain tissue. To accomplish this, a one end of a tube is inserted in the lateral ventricle while the other end is tunneled under the skin until it reaches the abdominal cavity. This is called a Ventriculo-peritoneal Shunt. It “shunts” excess CSF in the lateral ventricles downward, through the tube, into the abdominal cavity, where the peritoneum (the outer lining of the intestines and inner lining of the abdominal wall) reabsorbs it into the bloodstream. As CSF continues to be produced, when exit of the fluid is blocked, pressure in the ventricles increases and forces spinal fluid into the catheter and downward until it is released into the abdominal cavity. The peritoneum then reabsorbs CSF, and it passes into the blood stream.

Left untreated, hydrocephalus causes severe neurologic problems and ultimately death. Patients with ventricular-peritoneal shunts need frequent, close follow-up to prevent the catheter from clogging, becoming infected, or worsening the neurologic symptoms. Most patients are better after shunting. However, many patients regress over time as symptoms gradually worsen. If a cause for hydrocephalus can be found and corrected, those patients have a good chance of improving. Some do not.

As people live longer, the chances of developing hydrocephalus increase. If it is found early and treated appropriately, life expectancy is not affected.

References: Hochstetler A, Raskin J, Blazer-Yost BL. Hydrocephalus: historical analysis and considerations for treatment. Eur J Med Res 2022 Sep 1;27:168-232.